︎︎︎Info

Title

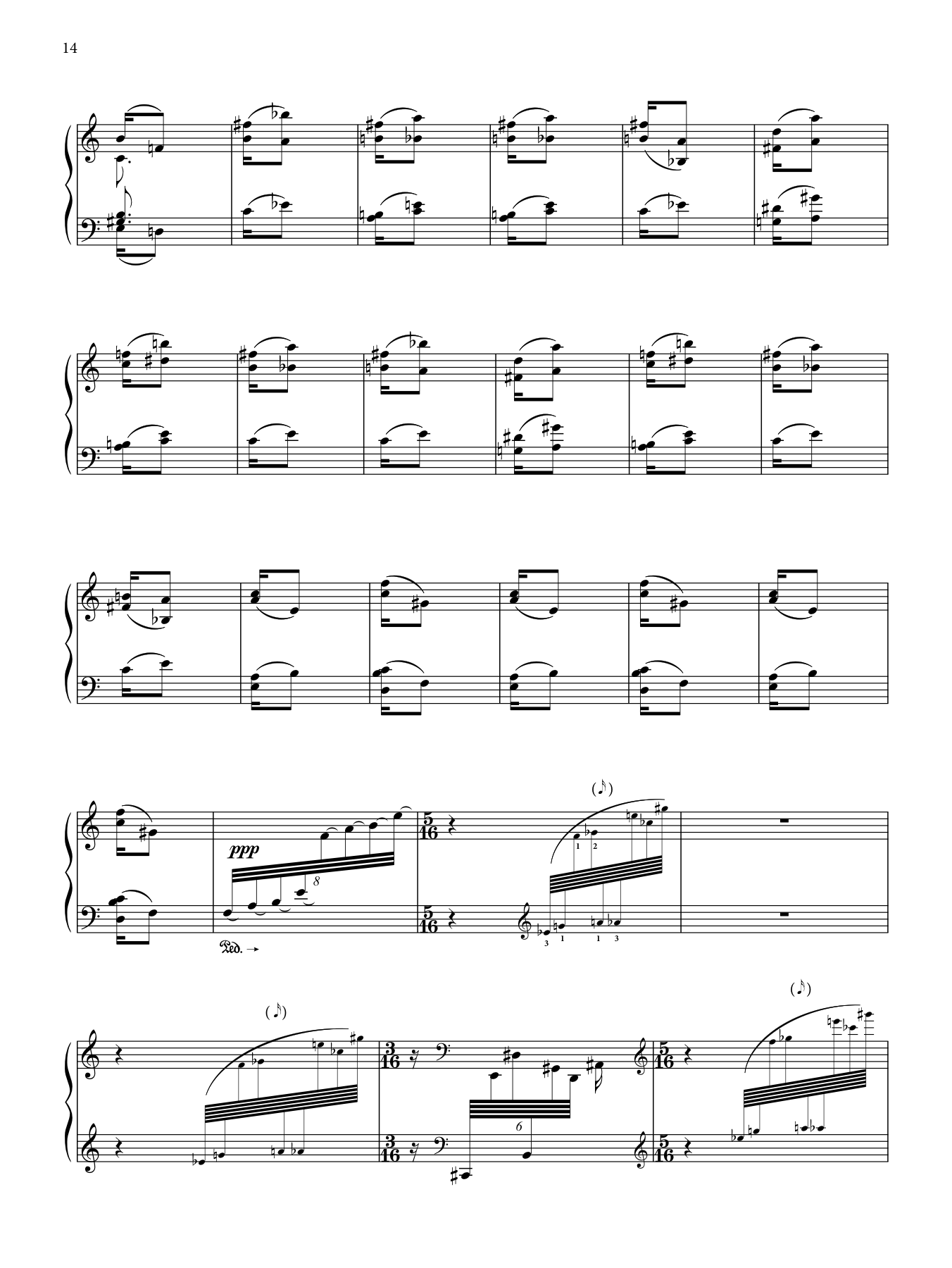

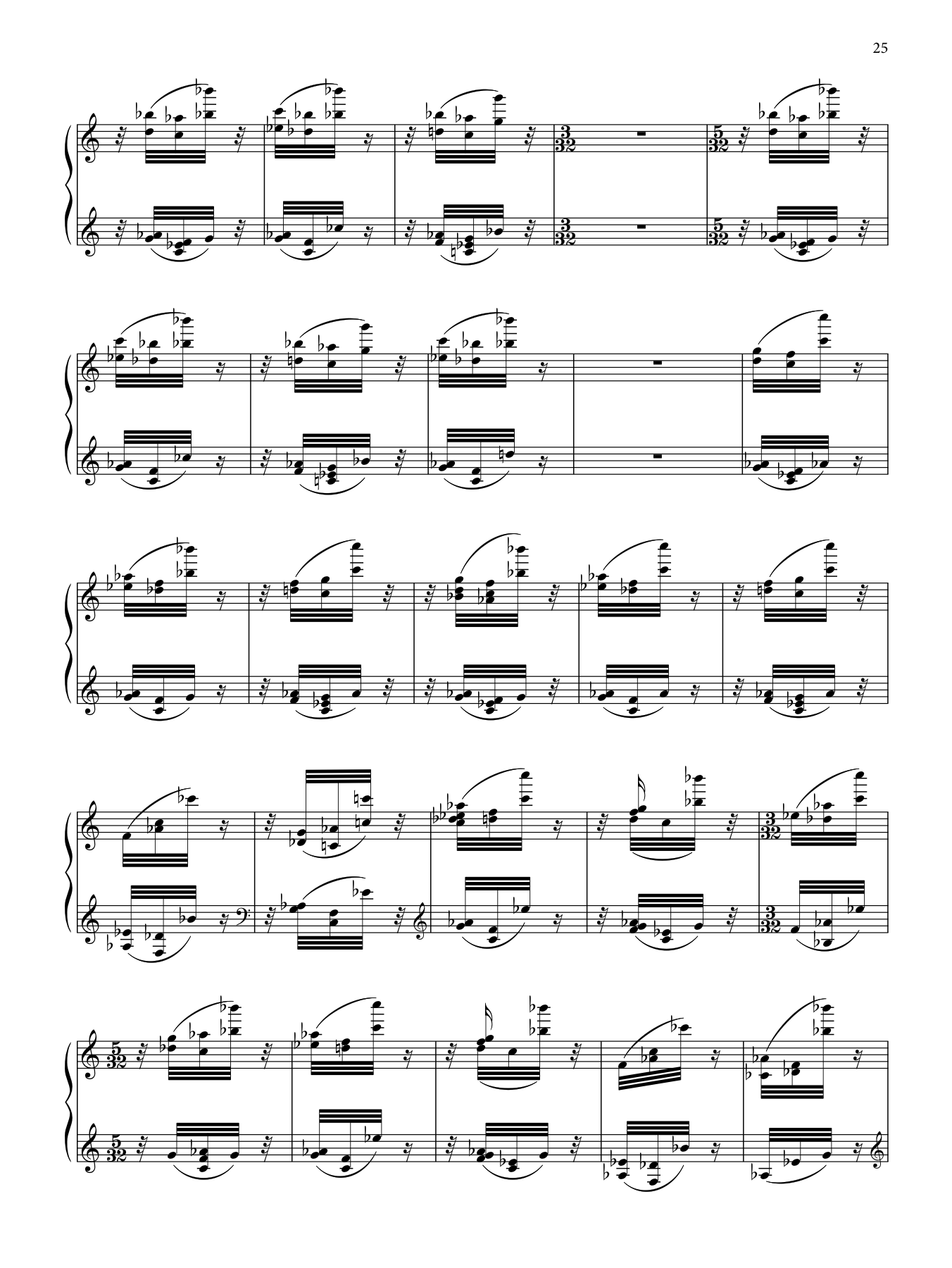

Obsessions

Inventory

pno solo

Year

2014

Duration

50’

Commission

R. Andrew Lee

Publisher

Recording

Premiere

April 17, 2015

Wayward Music Series

The Chapel, Seattle

R. Andrew Lee, piano

Wayward Music Series

The Chapel, Seattle

R. Andrew Lee, piano

︎︎︎Note

Eclecticism often suggests a grab bag: the frenetic postmodernism of John Zorn, the symphonic collages of Gustav Mahler. But the music of Adrian Knight instead exhibits two seemingly distinct, fully formed, and intriguing artistic personalities. There is the composer of still and beautiful piano works such as “Abide With Me,” which unfolds dreamily in the manner of Harold Budd, and long-form experiments with sine tones, like the transfixing “Världens Undergång.” And then there is, inexplicably, the cryptic songwriter and lead singer of garish nightlife bands, saturated with the supersonic glitter of 1980s New Wave. Though Knight’s “Obsessions”—a placid, repetitive, and ultimately haunting work for solo piano—initially resembles the former in sound, it is also saturated with the strange and violent spirit of the latter.

“Obsessions” is both absorbing and self-absorbed, its serenity betraying a darker impulse. “All my life I’ve struggled with bad habits, routines, patterns, obsessions,” Knight writes in a program note. “Whether a form of mild self-flagellation or a mindless desire for normalcy and structure, they rule my life…If the piece is about anything, it is about me, and it is about itself. It’s stuck in its own stupid routine. The fact that it ends is its only victory.” Even as Knight calls it a “stupid routine,” the music enchants more than it frustrates. In several extended sections, the composer develops on the phrases that open the piece, a sunken cathedral of rippling chords that alternate with silence. A couple minutes in, he unveils a “lamentation” motif: a drooping of two chords, punctured by rests, which he calls “the main obsession of the piece.” The music is developmental but never quite fully develops; it is a theme and variations, or perhaps a rondo, but cast as a kind of unhealthy fixation on a set of musical materials rather than an unfolding narrative.

When we met at a coffee shop in downtown Manhattan on a rainy day last December, Knight outlined his artistic biography. Born in Uppsala, Sweden, he began piano at age six but first absorbed music entirely by ear—including figuring out how to play Chopin waltzes by listening to his teacher—until his father bribed him with $50 to learn how to read notation. As soon as he could read music, he wanted to compose. He was the kind of teenager who gave a class presentation on the otherworldly music of Olivier Messiaen to a cohort of utterly perplexed eighth graders. He had no direct relationship to the new-music world and so he wrote letters to well-known composers, hoping to discover how one might join their ranks. At college in Stockholm, still influenced by Messiaen, he wrote in a densely gestural musical language, and soon concluded he was following the wrong path. “I realized that I had been not true to myself,” Knight told me. “I started from scratch and started writing in a more drone-inspired style, mostly diatonic but punctured here and there by dissonances and unresolved tensions. That’s when I felt like I was starting to get comfortable with an aesthetic.”

Knight has crystallized that approach over the past few years—while he attended Yale, launched the record label Pink Pamphlet, and continued to pursue his beguiling side career in lipstick-smeared pop projects such as “Pictures of Lindsey”—though “Obsessions” also points towards other horizons. He called it “a summary of a bunch of different directions that I’ve been trying out, what I like to think of as a harmonic labyrinth. There’s an equal-weightedness to each harmony, there’s a kind of push and pull that happens. I’m curious about chords that could go a number of different ways, and have a number of different types of functionality.”

Knight’s typical compositional approach is reminiscent of the self-critical Brahms, who burned many of his sketches and early compositions. He usually drafts a piece for several months, then throws it in the trash and starts all over again. “At that point it’s a little easier to work because I’ve made all these mistakes,” he said. But given the massive scope of “Obsessions,” there just wasn’t enough time to write a bad copy, scrap it, and begin anew. “I’m surprised that it came together at all,” Knight observed. “At some point it was impossible to backtrack, just start over…it wouldn’t be ready for another five years.”

“I let things be where they felt comfortable,” he said, describing the piece as “almost like a diary of routines.”

Indeed, the manic nature of the music was partially a result of its arduous compositional process. “It’s this thing that keeps coming back but it’s not really wanted,” he added. “It’s not needed; it’s an unnecessary element. You are not able to get rid of it. I guess the change happened because I got sick of it and I wanted to change it, but it still needed to be in there.” Material is dwelled upon, discarded, and returns; the music lilts, waltzes, rumbles, flows. “Obsessions” breathes the spirit of Knight’s compositional touchstones, including Feldman, Messiaen, and Tavener, in what he called “a gallery of influences.”

We wonder at what the embers of Brahms’s sketches might have revealed; perhaps his first attempts were more self-expressive, more directly emotional, than the cool rigor of his published compositions. (After all, he also burned his letters to Clara Schumann.) “Obsessions” is at once abstract and deeply felt. The compulsive repetitions of the music sound, at times, less peaceful than indignant, irritated, regretful. As Knight remarked, “It’s probably my most personal piece, because, like life, its trajectory wasn’t predetermined. All I knew was that it would have to end.”

—William Robin (Reprinted With Permission)

Eclecticism often suggests a grab bag: the frenetic postmodernism of John Zorn, the symphonic collages of Gustav Mahler. But the music of Adrian Knight instead exhibits two seemingly distinct, fully formed, and intriguing artistic personalities. There is the composer of still and beautiful piano works such as “Abide With Me,” which unfolds dreamily in the manner of Harold Budd, and long-form experiments with sine tones, like the transfixing “Världens Undergång.” And then there is, inexplicably, the cryptic songwriter and lead singer of garish nightlife bands, saturated with the supersonic glitter of 1980s New Wave. Though Knight’s “Obsessions”—a placid, repetitive, and ultimately haunting work for solo piano—initially resembles the former in sound, it is also saturated with the strange and violent spirit of the latter.

“Obsessions” is both absorbing and self-absorbed, its serenity betraying a darker impulse. “All my life I’ve struggled with bad habits, routines, patterns, obsessions,” Knight writes in a program note. “Whether a form of mild self-flagellation or a mindless desire for normalcy and structure, they rule my life…If the piece is about anything, it is about me, and it is about itself. It’s stuck in its own stupid routine. The fact that it ends is its only victory.” Even as Knight calls it a “stupid routine,” the music enchants more than it frustrates. In several extended sections, the composer develops on the phrases that open the piece, a sunken cathedral of rippling chords that alternate with silence. A couple minutes in, he unveils a “lamentation” motif: a drooping of two chords, punctured by rests, which he calls “the main obsession of the piece.” The music is developmental but never quite fully develops; it is a theme and variations, or perhaps a rondo, but cast as a kind of unhealthy fixation on a set of musical materials rather than an unfolding narrative.

When we met at a coffee shop in downtown Manhattan on a rainy day last December, Knight outlined his artistic biography. Born in Uppsala, Sweden, he began piano at age six but first absorbed music entirely by ear—including figuring out how to play Chopin waltzes by listening to his teacher—until his father bribed him with $50 to learn how to read notation. As soon as he could read music, he wanted to compose. He was the kind of teenager who gave a class presentation on the otherworldly music of Olivier Messiaen to a cohort of utterly perplexed eighth graders. He had no direct relationship to the new-music world and so he wrote letters to well-known composers, hoping to discover how one might join their ranks. At college in Stockholm, still influenced by Messiaen, he wrote in a densely gestural musical language, and soon concluded he was following the wrong path. “I realized that I had been not true to myself,” Knight told me. “I started from scratch and started writing in a more drone-inspired style, mostly diatonic but punctured here and there by dissonances and unresolved tensions. That’s when I felt like I was starting to get comfortable with an aesthetic.”

Knight has crystallized that approach over the past few years—while he attended Yale, launched the record label Pink Pamphlet, and continued to pursue his beguiling side career in lipstick-smeared pop projects such as “Pictures of Lindsey”—though “Obsessions” also points towards other horizons. He called it “a summary of a bunch of different directions that I’ve been trying out, what I like to think of as a harmonic labyrinth. There’s an equal-weightedness to each harmony, there’s a kind of push and pull that happens. I’m curious about chords that could go a number of different ways, and have a number of different types of functionality.”

Knight’s typical compositional approach is reminiscent of the self-critical Brahms, who burned many of his sketches and early compositions. He usually drafts a piece for several months, then throws it in the trash and starts all over again. “At that point it’s a little easier to work because I’ve made all these mistakes,” he said. But given the massive scope of “Obsessions,” there just wasn’t enough time to write a bad copy, scrap it, and begin anew. “I’m surprised that it came together at all,” Knight observed. “At some point it was impossible to backtrack, just start over…it wouldn’t be ready for another five years.”

“I let things be where they felt comfortable,” he said, describing the piece as “almost like a diary of routines.”

Indeed, the manic nature of the music was partially a result of its arduous compositional process. “It’s this thing that keeps coming back but it’s not really wanted,” he added. “It’s not needed; it’s an unnecessary element. You are not able to get rid of it. I guess the change happened because I got sick of it and I wanted to change it, but it still needed to be in there.” Material is dwelled upon, discarded, and returns; the music lilts, waltzes, rumbles, flows. “Obsessions” breathes the spirit of Knight’s compositional touchstones, including Feldman, Messiaen, and Tavener, in what he called “a gallery of influences.”

We wonder at what the embers of Brahms’s sketches might have revealed; perhaps his first attempts were more self-expressive, more directly emotional, than the cool rigor of his published compositions. (After all, he also burned his letters to Clara Schumann.) “Obsessions” is at once abstract and deeply felt. The compulsive repetitions of the music sound, at times, less peaceful than indignant, irritated, regretful. As Knight remarked, “It’s probably my most personal piece, because, like life, its trajectory wasn’t predetermined. All I knew was that it would have to end.”

—William Robin (Reprinted With Permission)

︎︎︎Score Excerpts